All about GPR and APX PUSH POP

Evolution of GPR (General-Purpose Register)

16-bit Processors and Segmentation (1978)

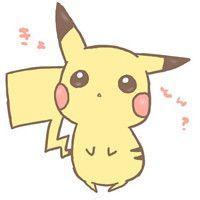

The IA-32 architecture family was preceded by 16-bit processors, the 8086 and 8088. The 8086 has 16-bit registers and a 16-bit external data bus, with 20-bit addressing giving a 1-MByte address space. The 8088 is similar to the 8086 except it has an 8-bit external data bus.

The 8086 has 8 more or less general 16-bit registers (including the stack pointer but excluding the instruction pointer, flag register and segment registers). Four of them, AX, BX, CX, DX, can also be accessed as twice as many 8-bit registers (see figure) while the other four, SI, DI, BP, SP, are 16-bit only.

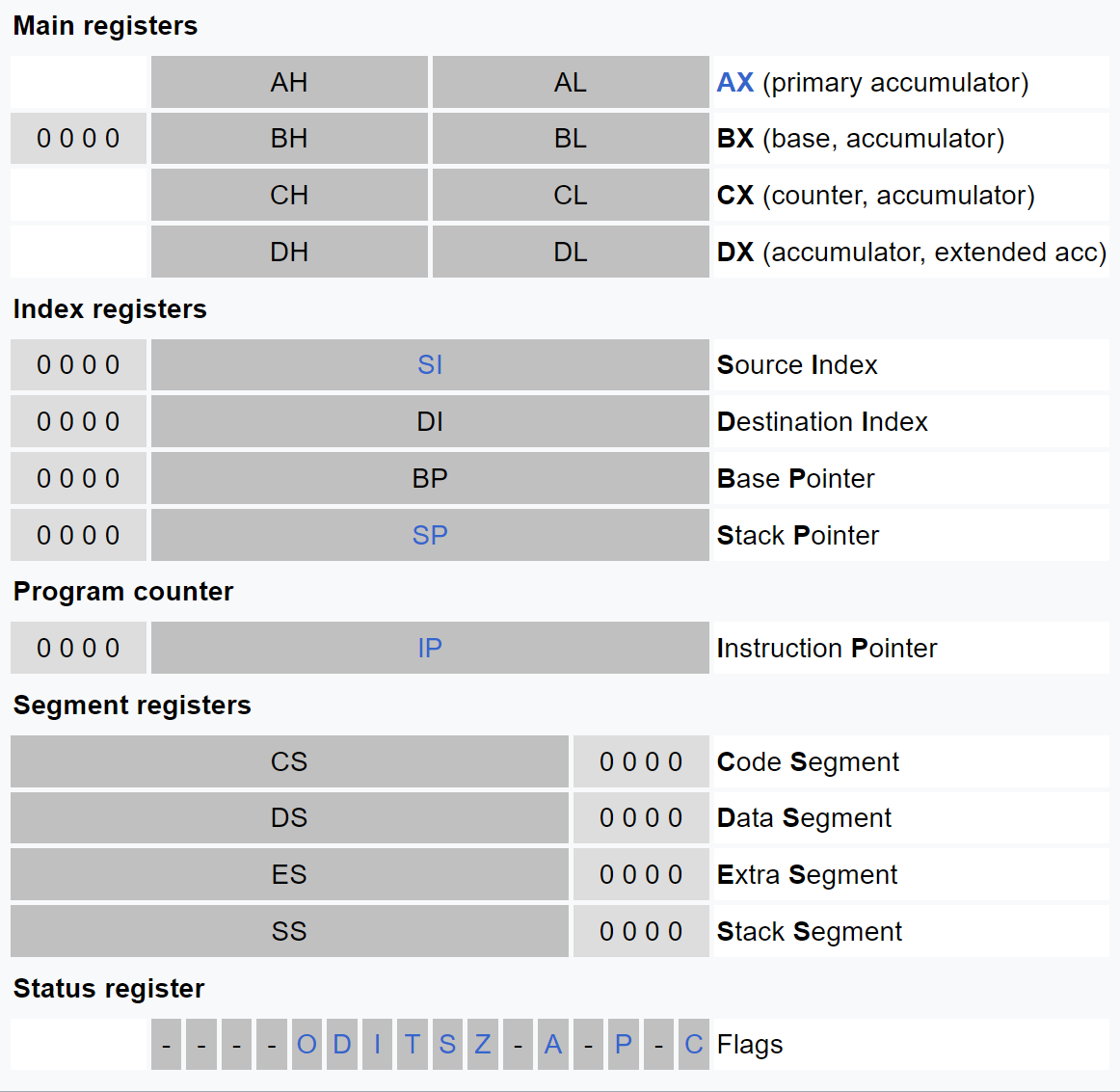

Note, the 20-bit addressing comes from segment << 4 + offset, e.g.

The Intel386 Processor(1985)

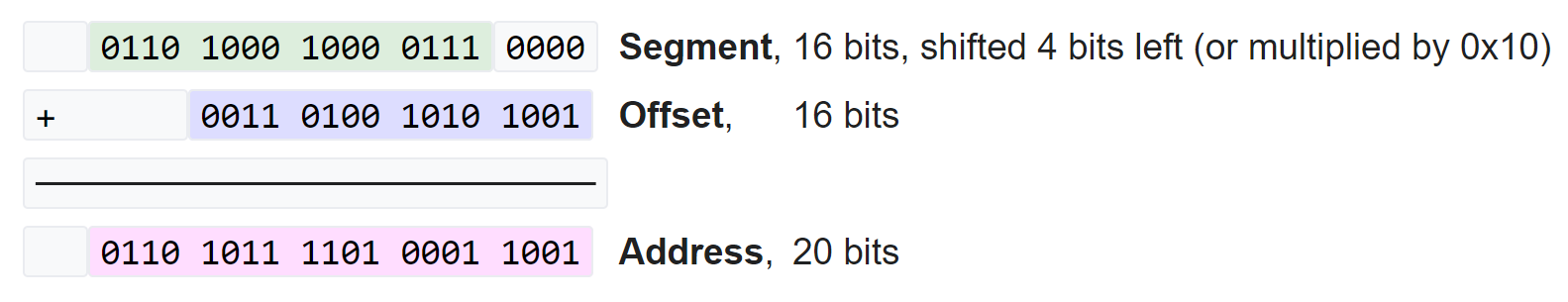

The Intel386 processor (i386) was the first 32-bit processor in the IA-32 architecture family. It introduced 32-bit registers for use both to hold operands and for addressing. The lower half of each 32-bit Intel386 register retains the properties of the 16-bit registers of earlier generations, permitting backward compatibility.

The higher half of the first four registers (AH, CH, DH and BH) is still accessible.

Two new segment registers have been added (FS and GS) for general-purpose programs, single Machine Status Word of 286 grew into eight control registers CR0–CR7. Debug registers DR0–DR7 were added for hardware breakpoints.

x86-64 (1999)

x86 (also known as 80x86 or the 8086 family) is a family of complex instruction set computer (CISC) instruction set architectures initially developed by Intel based on the Intel 8086 microprocessor and its 8088 variant.

x86-64 (also known as x64, x86_64, AMD64, and Intel 64) is a 64-bit version of the x86 instruction set, which introduced two new modes of operation, 64-bit mode and compatibility mode, along with a new 4-level paging mode.

Notable changes in the 64-bit extensions include:

64-bit integer capability

All general-purpose registers (GPRs) are expanded from 32 bits to 64 bits, and all arithmetic and logical operations, memory-to-register and register-to-memory operations, etc., can operate directly on 64-bit integers. Pushes and pops on the stack default to 8-byte strides, and pointers are 8 bytes wide.

Additional registers

In addition to increasing the size of the general-purpose registers, the number of named general-purpose registers is increased from 8 (i.e. EAX, ECX, EDX, EBX, ESP, EBP, ESI, EDI) in x86 to 16 (i.e. RAX, RCX, RDX, RBX, RSP, RBP, RSI, RDI, R8, R9, R10, R11, R12, R13, R14, R15). It is therefore possible to keep more local variables in registers rather than on the stack, and to let registers hold frequently accessed constants; arguments for small and fast subroutines may also be passed in registers to a greater extent.

Instruction pointer relative data access

Instructions can now reference data relative to the instruction pointer (RIP register). This makes position-independent code, as is often used in shared libraries and code loaded at run time, more efficient.

Intel Advanced Performance Extensions (2023)

Advanced Performance Extensions (APX), also known as Intel Advanced Performance Extensions (Intel APX), are extensions to the x86 instruction set architecture (ISA) for microprocessors from Intel doubling the number of general-purpose registers from 16 to 32 and adding new features to improve general-purpose performance.

Registers R16, R17, R18 and so on up to R31 are added to GPRs. This allows the compiler to keep more values in registers; as a result, APX-compiled code contains 10% fewer loads and more than 20% fewer stores than the same code compiled for an Intel 64 baseline. Register accesses are not only faster, but they also consume significantly less dynamic power than complex load and store operations.

System V x86-64 Calling convention about GPR

In computer science, a calling convention is an implementation-level (low-level) scheme for how subroutines or functions receive parameters from their caller and how they return a result. When some code calls a function, design choices have been taken for where and how parameters are passed to that function, and where and how results are returned from that function, with these transfers typically done via certain registers or within a stack frame on the call stack. There are design choices for how the tasks of preparing for a function call and restoring the environment after the function has completed are divided between the caller and the callee.

Callee-save or Caller-save

The calling convention of the System V x86-64 ABI is followed on Solaris, Linux, FreeBSD, macOS, and is the de facto standard among Unix and Unix-like operating systems. RBX, RBP, RSP, and R12-R15 are callee-saved registers. In other words, a called function must preserve these registers’ values for its caller. Remaining registers (RAX, RCX, RDX, RSI, RDI, R8-R11, R16-R31) are caller-saved registers.

Argument passing

Arguments of types (signed and unsigned) _Bool, char, short, int, long, long long and pointers are in INTEGER class. (Arguments of types _Float16, float, double, _Decimal32, _Decimal64 and __m64 are in SSE class.)

When passing argument, if the class is INTEGER, the next available register of the sequence %rdi, %rsi, %rdx, %rcx, %r8 and %r9 is used. (If the class is SSE, the next available vector register is used, the registers are taken in the order from %xmm0 to %xmm7.)

APX PUSH/POP

Motivation

- Reduce the cost of register save/restore operations (stack push/pop)

- Enables compiler to aggressively utilize 32 GPRs without being throttled by save/restore overhead concerns

PUSH2/POP2

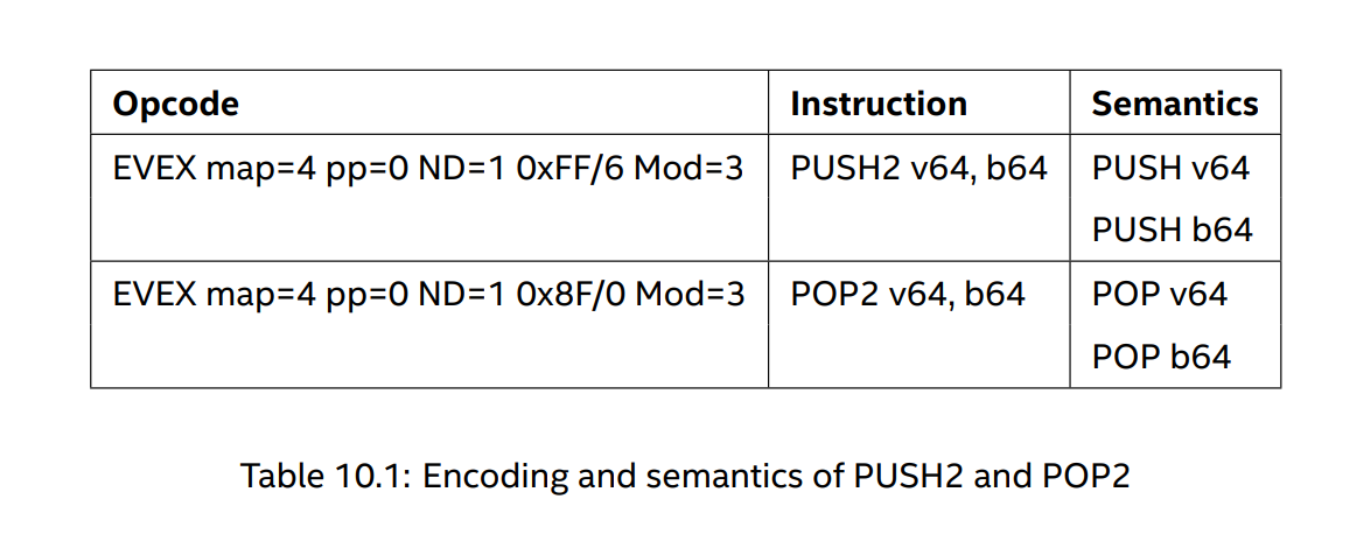

PUSH2 and POP2 are two new instructions for (respectively) pushing/popping 2 GPRs at a time to/from the stack.

The opcodes of PUSH2 and POP2 are those of PUSH r/m and POP r/m from legacy map 0, but we require ModRM.Mod = 3 in order to disallow memory operand. (A PUSH2 or POP2 with ModRM.Mod ̸= 3 triggers #UD (Undefined instruction).) In addition, we require that EVEX.ND = 1, so that the V register identifier is valid and specifies the second register operand.

The encoding and semantics of PUSH2 and POP2 are summarized in the table above, where b64 and v64 are the 64b GPRs encoded by the B and V register identifiers respectively. The osize of PUSH2 and POP2 is always 64b. The semantics is given in terms of an equivalent sequence of simpler instructions. We require further that neither b64 nor v64 be RSP and, for POP2, b64 and v64 be two different GPRs. Any violation of these conditions should trigger #UD. The two register values being pushed are either both written to memory or neither one is written, but the two writes are not necessarily atomic.

The data being pushed/popped by PUSH2/POP2 must be 16B-aligned on the stack. Violating this requirement should trigger #GP (general-protection exception).

Balanced PUSH/POP Hint

A PUSH and its corresponding POP may be marked with a 1-bit Push-Pop Acceleration (PPX) hint to indicate that the POP reads the value written by the PUSH from the stack. The processor tracks these marked instructions internally and fast-forwards register data between matching PUSH and POP instructions, without going through memory or through the training loop of the Fast Store Forwarding Predictor (FSFP). Instead, a more efficient memory-renaming optimization can be used.

The PPX hint is encoded by setting REX2.W = 1 and is applicable only to PUSH with opcode 0x50+rd and POP with opcode 0x58+rd in the legacy space. It is not applicable to any other variants of PUSH and POP.

The PPX hint requires the use of the REX2 prefix, even when the functional semantics can be encoded using the REX prefix or no prefix at all. Note also that the PPX hint implies OSIZE = 64b and that it is impossible to encode PPX with OSIZE = 16b, because REX2.W takes precedence over the 0x66 prefix.

Similarly, PUSH2 can be marked with a PPX hint to indicate that it has a matching POP2, which is also marked. The PPX hint for PUSH2 and POP2 is encoded by setting EVEX.W = 1. We require that EVEX.pp = 0 in PUSH2 and POP2 and their OSIZE always be 64b.

Note that for PPX to work properly, a PPX-marked PUSH2 (respectively, POP2) should always be matched with a PPX-marked POP2 (PUSH2), not with two PPX-marked POPs (PUSHs).

The PPX hint is purely a performance hint. Instructions with this hint have the same functional semantics as those without. PPX hints set by the compiler that violate the balancing rule may turn off the PPX optimization, but they will not affect program semantics.

Code Generation Guidelines

Background for stack frame

// a.c

void f() {

asm volatile("":::"rbx", "r12", "r13", "r14", "r15");

}

void g() { f(); }

$ gcc -S a.c -o -

f:

# RSP = 16*n + 8

pushq %rbp

# RSP = 16*(n+1)

movq %rsp, %rbp

pushq %r15

pushq %r14

pushq %r13

pushq %r12

pushq %rbx

nop

popq %rbx

popq %r12

popq %r13

popq %r14

popq %r15

popq %rbp

ret

g:

pushq %rbp

movq %rsp, %rbp

movl $0, %eax # RSP = 16*n

# CALL instruction peforms two operations

# 1. pushes the address of next instruction (RIP) on the stack

# 2. change RIP to the call destination

call f

nop

popq %rbp

ret

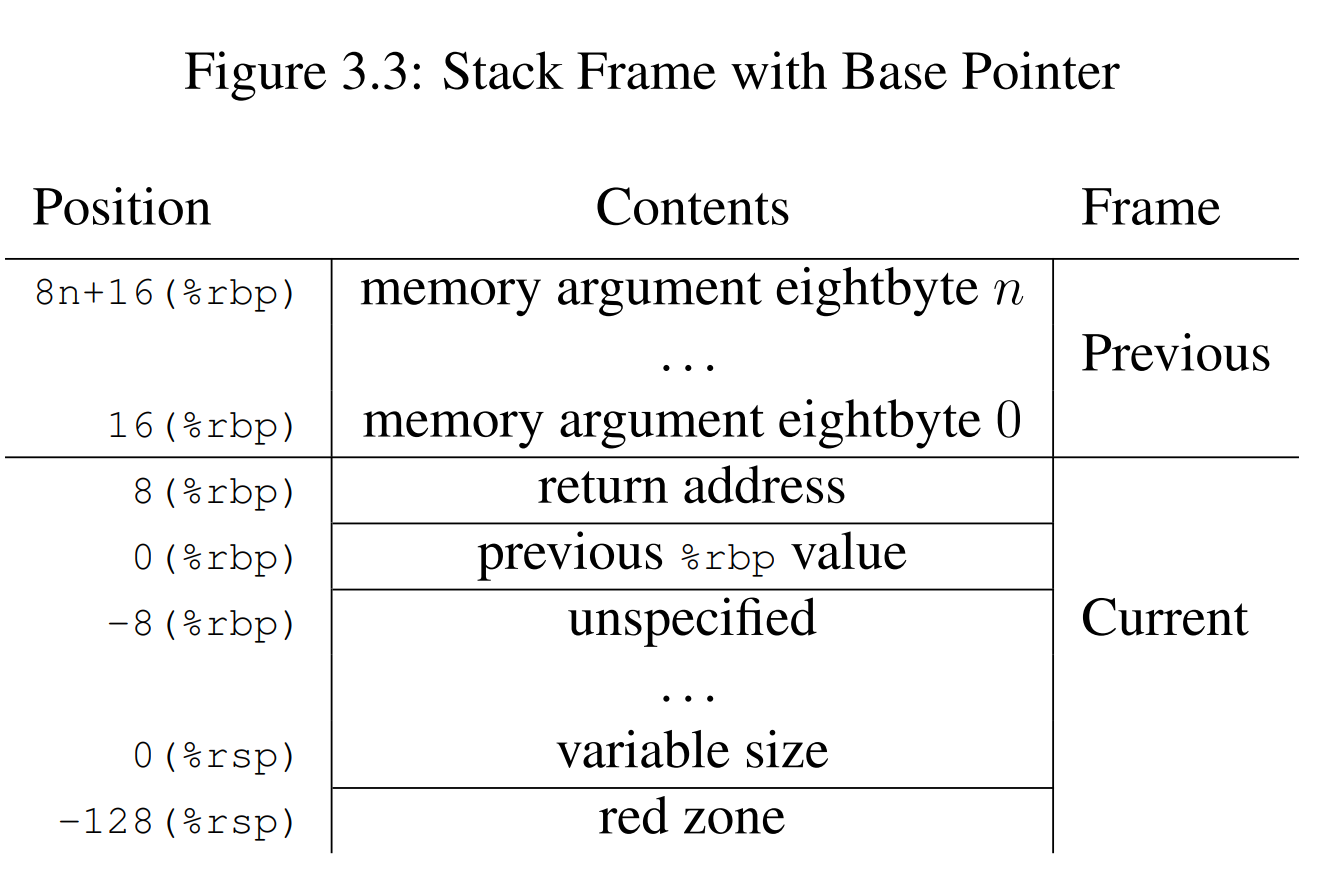

Each function has a frame on the run-time stack. This stack grows downwards from high addresses. The above figure shows the stack organization. The end of the input argument area shall be aligned on a 16 (32 or 64, if __m256 or __m512 is passed on stack) byte boundary. In other words, the stack needs to be 16 (32 or 64) byte aligned immediately before the call instruction is executed. Once control has been transferred to the function entry point, i.e. immediately after the return address has been pushed, %rsp points to the return address, and the value of (%rsp + 8) is a multiple of 16 (32 or 64).

The 128-byte area beyond the location pointed to by %rsp is considered to be reserved and shall not be modified by signal or interrupt handlers. Therefore, functions may use this area for temporary data that is not needed across function calls. In particular, leaf functions may use this area for their entire stack frame, rather than adjusting the stack pointer in the prologue and epilogue. This area is known as the red zone.

PUSH2/POP2

General speaking, when the frame pointer is on, i.e.

pushq %rbp

movq %rsp, %rbp

is in the prologue, %rsp at the first PUSH for non-RBP is a multiple 16; when the frame pointer is omitted, (%rsp + 8) at the first PUSH is mulitple of 16. With PUSH2/POP2, the above code can be optmized to

$ gcc -S a.c -o -

f:

# RSP = 16*n + 8

pushq %rbp

# RSP = 16*(n+1)

movq %rsp, %rbp

pushq %r14, %r15

pushq %r12, %r13

pushq %rbx

nop

popq %rbx

popq %r13, %r12

popq %r15, %r14

popq %rbp

ret

To the get the best performance, the strategy of using PUSH2 should be

- Not use push2 when there are less than 2 pushs.

- Not use push2 when there are 2 pushs and the stack is not 16B aligned.

- When the number of CSR push is odd

- Start to use push2 from the 1st push if stack is 16B aligned.

- Start to use push2 from the 2nd push if stack is not 16B aligned.

- When the number of CSR push is even, start to use push2 from the 1st push and make the stack 16B aligned before the push

PPX

POPXreads its data from a prior matchingPUSHX(and from no other store)POP2Xalways needs to read fromPUSH2X

If either guideline is violated, then there may be a loss of performance upside – but:

- Performance is never worse than with legacy

PUSH/POP - No difference in functional semantics

Reference

- https://software.intel.com/en-us/articles/intel-sdm

- https://www.intel.com/content/www/us/en/developer/articles/technical/advanced-performance-extensions-apx.html

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/I386

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Intel_8086

- https://en.wikibooks.org/wiki/X86_Assembly/X86_Architecture

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/X86-64

- https://gitlab.com/x86-psABIs/x86-64-ABI